You wouldn’t think so when looking into those beautiful black eyes, but harbour seals are wild predators! Their sharp teeth and streamlined body are perfect for hunting fish. Harbour seals are the most prominent seal speceis in the Wadden Sea. During low tide, they lie on the sandbanks in the sun and to rest. In the summer, they give birth and nurse their young. These seals are called harbour seals because they used to follow schools of fish into harbors.

Distribution and habitat of harbour seals

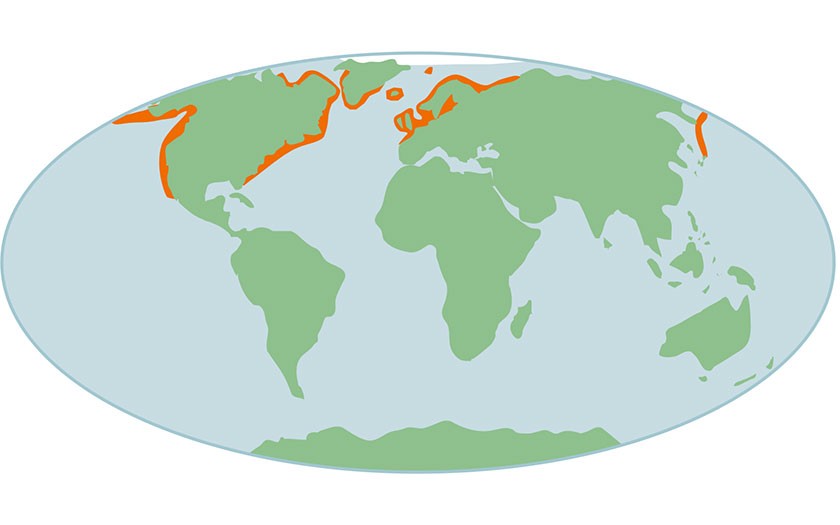

Because you rarely see harbour seals in open sea, you would think that they are basically coastal animals. However, research using transmitters attached to seals have shown that they often swim more than 100 kilometers seaward. So they regularly swim in open sea but because they are mostly under water, they aren’t often spotted. The harbour seal is found along almost all coasts of the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and bordering seas. They have a particular preference for tidal regions and river mouths, where deserted sandbanks or stones are exposed during low tide.

Seals in fresh waters

Seals have no problem living in brackish or fresh water, as long as there is enough fish. Seals used to swim upriver more often. However, since most Dutch rivers are now shut off by sluices and dams, it’s not that easy to reach inland waters anymore. Nevertheless, it still happens. Seals are regularly spotted in the closed freshwater IJsselmeer and in the major rivers. The most adventurous have even reached Maastricht. In order to achieve that, the animals must have slipped through sluices while boats were passing through or when the gates were slightly open. After a period of time, they swim back or let themselves flow back to sea when waterways are drained.

Photos and reports from eyewitnesses tell us that seals have no problems finding food in fresh water. There is a photo of a harbour seal indulging on a huge pike. Other seals have been photographed with perch, carp and eel. Large prey eaten above water is easy for people passing by to see. Smaller prey is more difficult, since they are swallowed under water. No one sees it happening. For the first time ever, scientists have studied the stomach of a harbour seal that had died in fresh water. This animal had eaten mainly flounder, smelt and river lamprey in the IJsselmeer. These are species which could have been caught in the Wadden Sea as well.

Reproduction of harbour seals

Female harbour seals are sexually mature at age 4; males are only mature at age 6. They mate from early August to mid September. Although the pregnancy of the harbour seal lasts for 11 months, the implantation is delayed during the first months. A fertilized egg enters the womb after three months and then begins to grow. The actual pregnancy is only around 7 to 8 months.

Pups are born during low tide on exposed sandbanks. They need to be able to swim almost immediately, as the tide rises. The pups drink milk from the mother for three weeks and in this period, the pups grow from 10 to 24 kilograms. They grow so quickly because the mother’s milk is very nutricious and has a fatty content of 45%. When nursing, the mother and pup lie on a sandbank during low tide. The nursing usually takes place at the same time that people are the most active on the mud-flats with boats and mud-flat hikes. That is why special haul-out areas have been established, where people are forbidden to enter during the birthing and nursing period. This way, the young can nurse undisturbed with its mother and gain lots of weight. After the nursing period, the mother leaves her pup who must now fend for itself. It must find its own food and learn to catch fish. That extra weight is necessary because most young seals need time to become handy at catching a meal.

Seal diet

Seals eat mostly what’s available at the time. However, each seal seems to have its own preference for specific species of fish. Therefore, the variation is large and their diet changes with every season. They prefer to eat fish that live close to the bottom, such as flatfish, cod species, gobies and lesser sandeel. Adult seals that live off of flatfish, need to eat up to 8 kilograms per day. Animals in captivity are fed fattier fish, such as mackerel or herring, and therefore eat only an average of 3 to 4 kilograms per day.

Population in the Dutch Wadden Sea

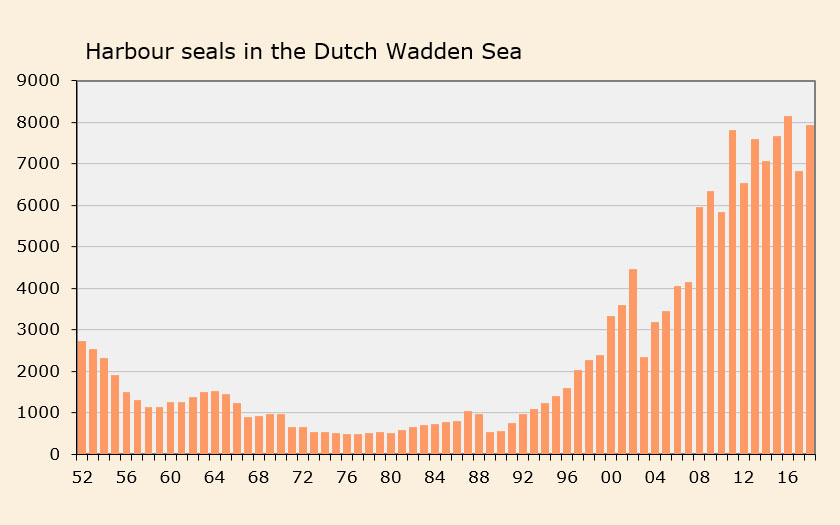

The number of harbour seals has been growing rapidly in recent years. In 2018, 7925 harbour seals were counted in the Dutch wadden region. Scientists assume that one third of the seals are underwater during a count, so the total population is an estimated 30% more. The history of the population of harbour seals in the Dutch Wadden Sea has had peaks and drops, caused by hunting, pollution and disease.

Around 1950, approximately 3000 harbour seals swam in the Wadden Sea. Because in those days it was believed that the seal was a serious competitor for the fishermen, 500 to 600 animals were shot every year. Furthermore, it was the fashion in those days to wear furs from young seals so many young animals were killed, continually diminishing the seal population. By the end of the 1950s, there were only around 1000 animals still alive. Hunting seals in the Netherlands was forbidden in 1962. As can be seen in the graph, the population grew steadily till 1965.

Then another decline occurred; this time the cause was polluted seawater. Especially harmful, PCBs appeared to have a negative influence on the reproduction of the seals. Up till the mid 1970s, the numbers continued to diminish to an absolute low of approximately 500 animals. When PCBs were banned and hunting seals in Germany forbidden, the population slowly recovered, reaching approximately 1000 specimen in 1987. The work of the two Dutch seal sanctuaries, Ecomare and the seal crèche Pieterburen, also helped restore the population.

The graph shows two epidemics effecting the seals: in 1988 and 2002. Many seals died during these epidemics, but after both periods, the population recovered quickly. In the summer of 2003, directly after the epidemic of 2002, around 2350 harbour seals were counted on Dutch sandbanks and tidal flats in the wadden region. Five years later, the popluation had almost doubled in size. That is why in 2008, the international Trilateral Seal Expert Group (TSEG) concluded that the seals in the Wadden Sea had completely recovered from the epidemic in 2002.

Population of seals in the International Wadden Sea

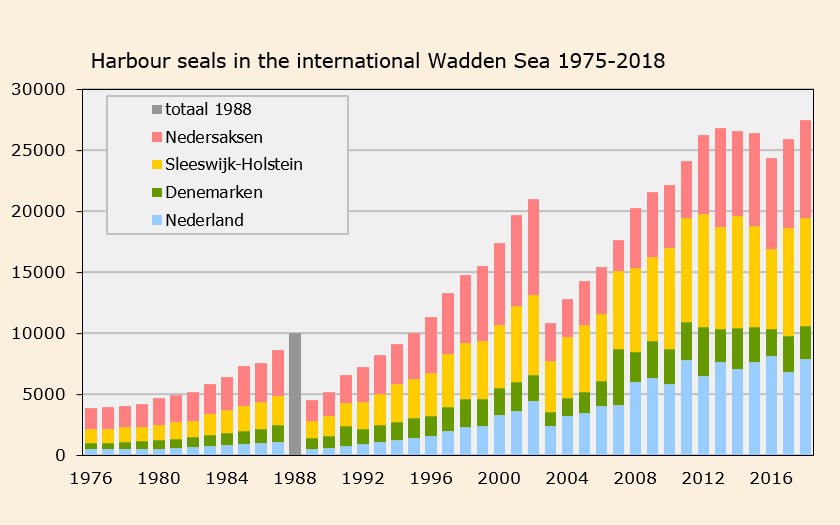

Every year, the number of seals in the entire wadden region are counted. In 2018, there was a total of 27,492 harbour seals counted in the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, of which 9285 were pups. The seals are counted during low tide, when most of the animals lie on the sandbanks. One third of the seals are likely swimming during the count, so that this amount must be accounted for in the total. That is why the total amount in the entire Wadden Sea is estimated at approximately 40,000 animals. In the graph, you can see how many seals have been counted since 1975. You can clearly recognize the two virus epidemics, one in 1988 and the other in 2002.

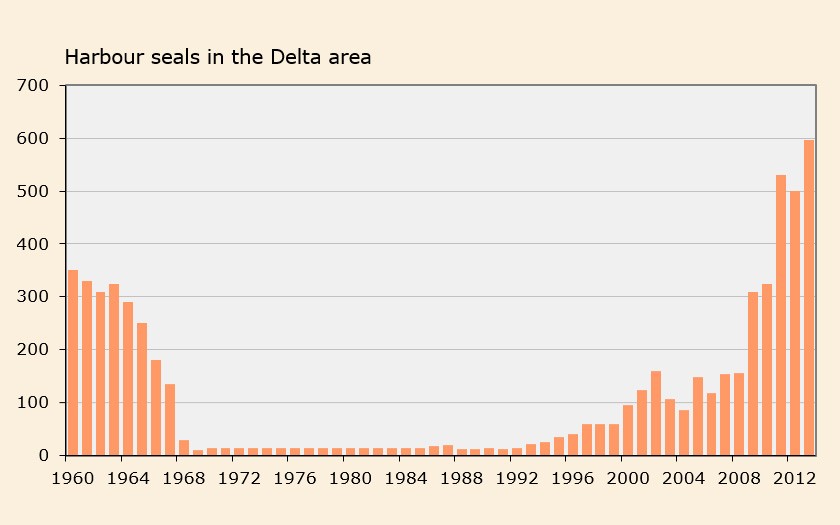

Population of harbour seals in the delta region

There used to be a large population of seals in the Dutch delta region. Based upon the number of seals shot at the beginning of the 20th century, the seal population here was between 6000 and 12,000 animals. In the preceding centuries, hunters in the delta caught hundreds of seals yearly, but the population was apparently large and strong enough to make up for the loss. Around 1935, the seals were counted for the first time, around 1300 animals. The population had declined due to hunting with rifles.

Just like the Wadden Sea, the delta region was also an important area for the harbour seal in the Netherlands. Unfortunately, life for the seals in the delta region declined. In 1990, there were only 14 seals. This was probably related to the heavy pressure from hunting up till 1961, followed by very poor water quality in the area. In addition, recreation, tourism, fisheries and shipping continued to increase, which continually disturbed the seals. They also lost a large part of their habitat when the Delta Works were built. Since 1994, life for the seals in the delta slowly started to improve. More than 150 seals were counted in 2005 and 456 seals in 2013. Food is not a limiting factor for the animals. In the adjacent Voordelta and North Sea coastal zone, there is the same amount or even more fish than in the Wadden Sea.

Seal behavior and studies with transmitters

People at sea often see seals lying in groups along the shore or on tidal flats. That’s why for a long time, we used to believe that the seals were strongly bonded to these banks and shores. But when a number of seals were tagged with a transmitter, it became clear that seals swim over a large area, and they don’t only stay in the vicinity of their haul-out areas.

Wageningen Marine Research is working in the Netherlands to study seals with transmitters. The first group of nine seals were provided with transmitters placed on their heads in 1997. The seals were born in captivity and released in the Briels Channel, in the South-Holland delta region. From these transmitters, the scientists received information concerning seal behavior: where do they go to hunt, where are their preferred haul-outs, do they wander far away and if so, where to?

Nowadays, also wild seals are equipped with transmitters. Scientists want to learn more about the areas that are important for seals and whether the seals are affected by human activities, such as target practice or ramming. The transmitters are attached to the seal’s fur. When the seal molts, the transmitter falls off. Newer technique means smaller transmitters so they are now placed in the neck instead of on the head.

Harbour seals and virus epidemics

In 1988 and 2002, the harbour seals in the North Sea and wadden region were infected with a virus. Both times, more than half of the harbour seal population in the Dutch Wadden Sea died. Although the seal virus is not dangerous to people, it is always a good idea to stay away from a sick or dead seal. Dead animals can carry other germs that are harmful for our health. In addition, some seal diseases can also be contagious for dogs.

Seals on Texel

You can see harbour seals on Texel at Ecomare, but you also see them in the wild along the North Sea coast, the wadden dike and by the lighthouse.

Facts about harbour seal

- size:

Male: maximum 1.90 meter

Female: maximum 1.70 meter

- weight:

Male: maximum 170 kilogram

Female: maximum 130 kilogram

- color:

Gray with dark spots

- age:

Maximum around 35 years

- food:

Mostly fish (around 4 to 8 kilograms per day)

- movement:

Swimming and hobbling

- enemies:

Humans (disturbance, hunt, pollution and by-catch in fykes and fishing nets)

- reproduction:

Mature: betwee 2-5 years

Pregnancy: 10-11 months

Time of birth: summer(May, June, July)

Names

- Ned: Gewone zeehond

- Eng: Harbour seal (common seal, sand seal)

- Fra: Phoque veau marin

- Dui: Gemeiner Seehund

- Lat: Phoca vitulina vitulina

- Dan: Spættede sæl

- Nor: Steinkobbe (kobbe, sel, selhund)