Seals

Seals are the acrobats of the sea, but they are very clumsy on land. With its cute, round eyes, seals see very well under water. However, they would need eyeglasses to see sharply above water. Seals are completely adapted to life under water. Nevertheless, you can spot them regularly on the surface. They like to lie in the sun while resting on a sandbar or beach.

Seal diet

Seals eat primarily fish. They use their whiskers for locating prey in these predominantly turbid waters. Seals can feel the slightest movements in the water. In that way, seal can ‘see’ in turbulent water where the fish are, up to a distance of 100 meters. They can also determine the size and shape of the fish from a distance. Seals do not have a preference for one specific fish species, but they usually catch fish that live close to the sea bottom. Flatfish, lesser sandeel and cod species are their favorite food, although what they eat can vary per season, depending upon what’s available. Young seals must teach themselves to eat and catch fish after nursing ends. Their mother doesn’t teach them the tricks. In this period, young seals lose a lot of weight. But eventually, most of them learn it on time.

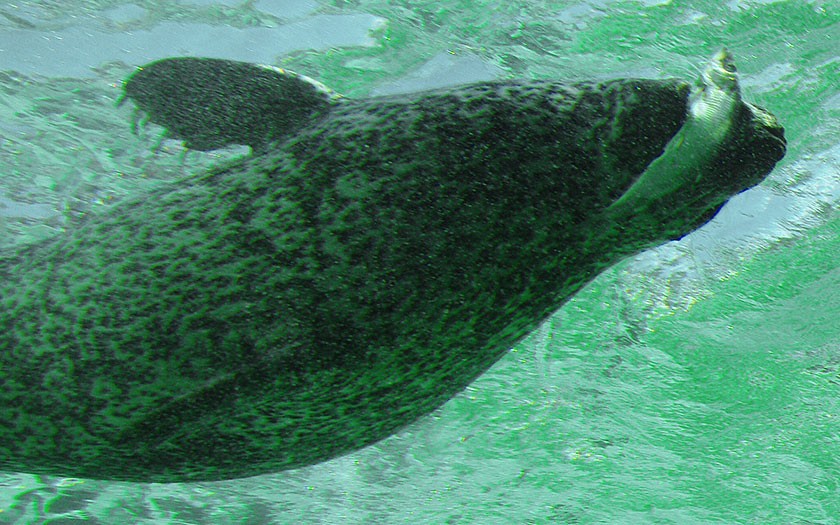

Seals in the water

A seal swims just as readily on its back as on its belly, standing upright or upside down. The front flippers serve as paddles; the body and hind fins provide the propulsion.

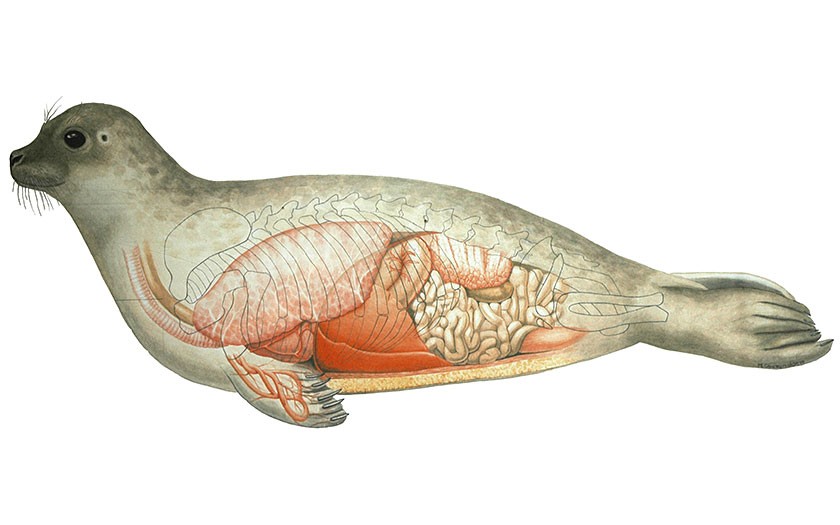

Seals can dive down to depths of hundreds of meters. During the first few minutes, they swim actively downwards, after which they go into a kind of gliding flight while they sink even deeper. Their body is totally adapted to long and deep dives. Their blood can absorb much more oxygen than human blood. Furthermore, they can lower their heart rate tremendously during the dive, from 40 to less than 1 beat per minute. This means they don’t need to breathe as often. When they ascend from deep depths, they can pump out the inhaled air from the air sacs, preventing deadly nitrogen bubbles from entering the bloodstream. Once above water, the heart beat of a seal increases to 120 beats per minute in order to provide enough oxygen for the organs.

Seals on land

The ancestors of seals lived on land. But that is hard to notice nowadays when you see a seal on land. In the course of millions of years, they have adapted in all kinds of ways to life in the sea. All these adaptations have made them very clumsy on land. They can’t walk since their hind fins lie in extension of their body. Sea lions, on the contrary, can use their back fins more or less as ‘hind feet’. That is why they can walk much better than seals. Seals drag their body over the ground with the help of their front flippers, a movement referred to as hobbling.

How do seals sleep

Seals sleep in the water as well as on land. In the water, they sleep floating in a standing position, like a fishing bobber, or floating horizontally on the surface. Because they are sleeping and not actively swimming, they can stay under water much longer than when hunting for food. There are known incidents where seals stay under water up to half an hour, however on the average, their stay is not longer than fifteen minutes.

Seals are well insulated

Most parts of the seal are well insulated with a thick layer of blubber. Sometimes the layer is more than 5 centimeters thick. Only the flippers and head are without blubber. When it gets very cold, seals can pinch off the blood flow to their skin in order to preserve the heat. They also use their flippers to regulate the body temperature. There are blood vessels just under the skin in the webbed area, between the toes of the flippers. Blood flowing to the flippers is cooled down by blood returning to the body and enters the flippers at a lower temperature. Before returning to the body, it is warmed up by blood heading to the flippers.

By regulating the temperature in this way, seals always have cold feet! That is why, as soon as the sandbanks appear above the surface, they try to keep their flippers out of the water. In that way, they lose less heat and are warmed by the sun. When it gets too warm, they let their flippers and head bungle in the water to cool off.

Seals in a banana pose

On the sandbanks in the Wadden Sea, you often see the seals lying in a typical banana pose. They probably do this to keep their head and flippers high and dry (and therefore warm). Seals are well insulated with a thick layer of fat, with the exception of their head and flippers. When they lie on a dry spot but where they water still advances, they hold up these parts to keep them dry. And that is automatically a kind of banana pose.

Seal anatomy

How do seals drink and pee

Adult seals hardly ever drink. They get their fresh water that they need from the fish they eat. When they haven’t eaten for awhile, the water comes from burning their blubber. When living in the sea, they naturally ‘drink’ salt water occasionally. Their kidneys are specially adapted to separating that salt and ridding it via the urine. They pee, but sparsely. The urine is very concentrated and is sometimes saltier than the seawater.

Should you visit their haul out area, you can often see small pits in the sand where seals have lain. This is where they peed and the sand has washed away. You might possibly even detect whether or not it was a male or female by the position of this pit in relationship to the seal’s imprint. The penis opening of the male is relatively high up, just under the navel. With females, the opening is much closer to the tail.

Molting seals

Seals have hair to prevent dehydration and damage when on land. The short hair also helps to prevent the cold seawater reaching their skin as quickly. They molt every year. Harbor seals get a new coat in the summer, grey seals in March-April. In this period, they like to stay as dry as possible to allow the molting process to take place as quickly as possible. When it is very cold or the seals need to flee a lot into the cold water, the molting process is slowed down. The coldness closes the blood flow to the skin. The process decelerates when there is a lack of blood in the skin. That is why it is very important that seals are able to rest in peace on the sandbanks during the molting process.

Seals giving birth and nursing

Seals give birth on dry land. Harbor seals are born in the summer months, grey seals in the winter. That is why grey seal pups have a thick winter coat. They are very adorable with their long white hair but it is also a bit awkward. They can’t swim due to this heavy coat. The first few weeks of their life, grey seal pups remain on land. The mother returns regularly to nurse, which they do for an average of three to four weeks. During this time, the pups only drink milk; they don’t learn to fish. They are usually 10 kilos at birth and 40 kilos when they stop nursing. When their mother abandons them, the young seals must teach themselves that fish is edible and how to catch them.

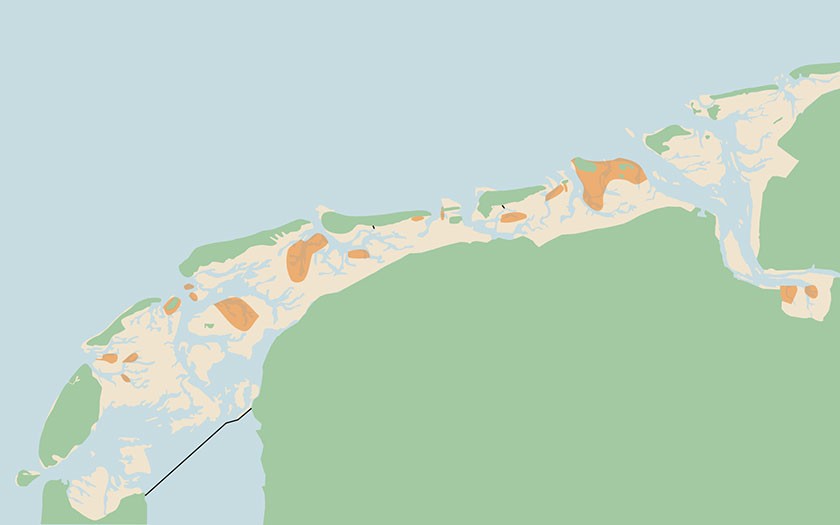

Seal distribution and population

The number of seals in the Wadden Sea region is well documented. Scientists from Wageningen Marine Research, (formally IMARES) count the seals in the Dutch Wadden Sea from an airplane by taking photos of them while lying on the sandbanks. One third of the population is then under water, so the scientists add 30% to the total counted in order to reach a final estimation.

Of the seals that inhabit the international wadden region (Netherlands, Germany and Denmark), the large majority are harbor seals, numbering around 40,000 in 2018 (adults and pups). However, harbour seals also inhabit other waters. In the North Sea area, they are found around the Scottish islands, in the Wash, along the English, French and Belgium coasts, in the Danish Skagerrak and along the southern coast of Norway.

Grey seals are found primarily around the Scottish islands, along the British east coast and in Cornwall. In December 1999, there was even a young seal seen in the Thames beyond London. In the Dutch Wadden Sea, a colony of grey seals was established in the 1990s. Since then, it has expanded into the largest colony in the entire Wadden Sea. In the Dutch Wadden Sea alone, a total of 4565 grey seals were counted in the winter of 2017-2018. The largest groups are located west of Terschelling, but small groups or individuals are sometimes seen elsewhere. The German islands of Helgoland and Amrum have colonies, numbering more than a hundred animals.

Satellite observations of seals with transmitters show that grey seals from the Wadden Sea can wander over the entire North Sea, and even swim from the Wadden Sea all the way to Scotland and back.

Seals can also survive in fresh water. They used to swim regularly upriver. Because most rivers are now closed off by sluices in the Netherlands, it’s no longer easy to reach fresh water. Nevertheless, it still happens. Seals are regularly spotted in the IJsselmeer. They probably entered through the sluices by the Afsluitdijk (Closure Dike). In 2011, a seal was hit by a car while hobbling over the Afsluitdijk.

Wandering seals from the north

In addition to the harbour seal and the grey seal, both indigenous to the southern North Sea, an occasional arctic seal species will wander into these regions. For example, ringed seals from the northern Baltic Sea and even harp seals are sometimes reported. In 1987, there was a small invasion of harp seals in the southern North Sea, caused by a lack of food in the Barents Sea.

Beaching of hooded seals have been reported but are much rarer. In 1986, several hooded seals washed ashore on the coasts of France, Belgium and the Netherlands. This ‘mini’ invasion was possibly related to a hunting party on the island of Jan Mayen in the northern Arctic Sea.

There was also the unique event of a stranding of a female bearded seal on 27 June 1988 in the harbor of Yerseke in Zeeland. Other strandings include six individual walrus beachings in the 20th century, the last one on Ameland in January 1998.

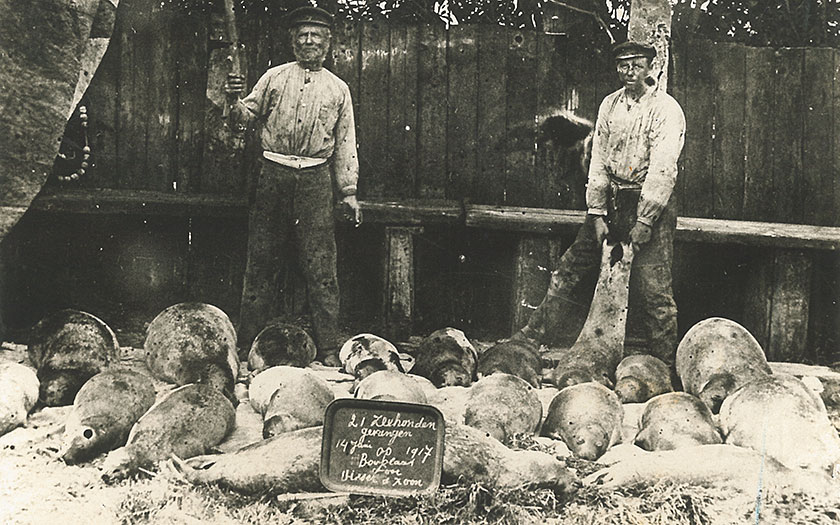

Human threats to seals

Seals were heavily hunted in the North Sea region in the past. They were considered pests. They damaged fishing nets and snatched fish away from the fishermen. Hunters received premiums for every seal shot. Despite the fact that hunting seals in the Wadden and North Seas ended more than 40 years ago and the seal population has grown, they are still threatened. The biggest threat facing seals nowadays is the flow of polluting waste materials from land to sea and from discharges and accidents at sea. In addition, disturbances from shipping and recreation are problems for the seals. Other threats include drowning in fykes and other fish nets.

Marine pollution and seals

Every day, large loads of disposed wastes flow into the North Sea. Originating from agriculture, industry and cities, these materials find their way via rivers which mouth in the North Sea. Other waste materials come from dumping and shipping accidents at sea, and via the air in the form of acid rain. Plankton absorbs the poison, which is how it enters the food chain. Eventually, they accumulate in marine mammals via the benthic animals and the fish. The concentrations of poison are highest in those species of animals living closest to the coastline. A well-known example of a dangerous poison for seals is PCBs. In the 1980s, many seals weren’t able to reproduce and were often sick from this toxin.

Seal threat: disturbing the peace

Another problem for seals in the North Sea and Wadden Sea is the increasing activity. Tourists and military activities disturb resting seals in the wadden region. This kind of disturbance is especially a threat during the summer when harbour seal pups are born. The young pups don’t get enough time to nurse or mother and young become separated. That is why seal reservations have been designated, where the animals must be left in peace. The water police take action against tourists that are getting too close to seals an average of four times a day. Seals are much less sensitive to disruption in the water than on land. They even tend to swim towards people.

Seal threat: drowning in fykes

Fish that swim into a fyke form an attractive prize for a seal. The seal will swim into the fyke to catch the fish. Once in the fyke, the seal cannot get out and drowns. Since 1994, all fykes in Dutch tidal waters are required to be equipped with a retaining net, specifically to keep out seals. This retaining net is a large-meshed net at the entrance to the fyke, through which eel and other fish can swim, but hold back seals. Nevertheless, seals are still drowning in fykes unequipped with the required retaining nets.

Seal versus fisherman

Fishermen consider seals a threat to the fisheries. In the past, premiums were offered for shooting seals due to the damage they supposedly caused. This argument is still used in Norway and Canada to rectify culling seals. From studies made of their stomach content and excrement, it appears that all Dutch harbour seals together consume less than (1-2%) what the fisheries bring on land. Harbour seals eat relatively young flounder, a fish species which is hardly commercially interesting for the fishermen.

Locally, standing rigging and fykes can be affected by hungry seals. The animals damage both the nets and the catch when stealing fish. Scottish and Norwegian salmon farms are also regularly visited by grey seals that are very fond of salmon. It is difficult to say what exactly the damage is because there are major discrepancies between what the fish farmers claim (‘enormous amount of damage’) and nature-lovers (‘damage practically negligible compared to the money earned by the farms’). Neutral sources say that the average damage is 1 to 4% of the total yield.

Seal protection in the Wadden Sea

Both the harbour seal and grey seal are on the Red List for mammals. When developing policy, the government and managing organizations are required to take seals into consideration and make sure that their population doesn’t decline.

In addition, a Seal Covenant was signed in 1988 in Bonn, Germany. This treaty between the three Wadden Sea countries, The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, regulates the protection of the seals in the Wadden Sea. Besides the ban on hunting, it was agreed to establish protected areas for the seals. Seal reservations were designated to prevent disruption to resting and nursing seals. These reservations are also closed areas in the summer, when the seal pups are birthed and nursed.

In other European waters, the harbour seal and grey seal fall under protection of the EU Habitat Directive (Appendix ll and V), the Bonn Convention (Appendix ll) and the Bern Convention (Appendix lll).