Seabirds

Whoever stands on the beach and looks out to sea usually sees birds. Gulls in particular are easily recognized by everyone. Nevertheless, they are more of a coastal bird. You don’t readily spot true seabirds from land, only during storm or as an oil victim. At sea, you could spot gannets, fulmars, auk species and kittiwakes. Most seabirds nest on rocky coast, in Scotland, northern England, Norway and the German island Helgoland. Sometimes they nest on drilling platforms. In the winter, they spread out over the North Sea, hunting for fish.

Superstition and seabirds

Seabirds have always appealed to our imagination. Seamen in earlier days had little more than the seabirds which followed their ships as companionship during their long voyages. They considered their presence during windless weather as a positive sign; it indicated that wind was on its way. Seabirds on the coast meant that storm was approaching. They also believed that the souls of deceased seamen continued living in seabirds.

With or without superstition, you observed seabirds with respect. They belong to a world in which people can only temporarily join with the help of artificial intervention.

Bird species in the North Sea

Around 300 species of seabirds are found in the oceans and seas throughout the world. In the North Sea region, there are around 10 common species: fulmars, gannets and auk species, kittiwakes and skuas. These birds only come on land to breed, especially on rocky coasts and cliffs. The only Dutch ‘grounds’ you’ll find seabirds nesting on are drilling platforms.

Sea-worthy birds

For warm-blooded animals such as birds, the sea is not an easy place to live. There is no protection in open sea. Seabirds have food reserves in the form of fat and heavy muscles. They also have a large stomach. A fulmar can carry 20 % of its body weight in food. To keep warm and dry, the seabirds have a perfect close-fitting plumage with a great ability to resist water.

Seabirds know how to use the salty seawater as drinking water. They can eliminate the salt from the seawater with the help of two glands situated on their scalp. Via a small canal, the excess salt is carried to the nostrils where it is excreted. You sometimes see a drop of salt hanging on the tip of the beak.

Seabirds lay only one egg a year, thereby only having to catch fish for one young. Even the long breeding period – usually more than a month – and the slow growth of the chick fits in. Young gannets are cared for at least three months before leaving the nest for good. Seabirds can grow to middle age. As opposed to most land birds, on the average seabirds only mature after 5 years. They are excellent flyers and swimmers, but aren’t very handy on land. That’s why they like to nest on the most inaccessible cliffs.

Seabirds and the art of hunting

Many seabirds eat fish. The birds have developed various hunting methods to catch their prey. Razorbills, guillemots and puffins dive deep under water. Not only do they look like penguins, they also have the same manner of ‘flying’ under water, with half-open wings. They have webbed-feet which serve as a rudder. Guillemots have been spotted at depths of 180 meters.

The gannet tracks its prey from the air and catches it by making a so-called jabbing dive: the animal dives from a height of 30 meters in a position perpendicular to the sea surface. With a speed of 100 km per hour and wings folded back against its body, it cleaves through the water surface like a living torpedo. The skull is specially strengthened and there’s a protective air cushion under the skin to absorb the enormous blow.

The fulmar is a surface hunter. While sitting on the water, it picks up fish waste or small fish and shrimp which swim just under the water surface.

Many birds have white-colored feathers covering their bellies. This color serves as camouflage. When the birds swim on the surface or fly just above, the fish have a difficult time distinguishing them from the glittering water surface. One exception is the common scoter. This bird eats shellfish and therefore has no need of camouflage.

Distribution of seabirds in the North Sea

It’s not easy to count seabirds in open water. Nevertheless, various research vessels have done it. Via a combination of observations and calculations, it’s possible to make a reasonable estimate.

It’s easier to map the breeding areas. Every year, these nests are counted on the Orkney and Shetland Islands along the northeastern British coast and on the German island Helgoland.

Seabirds breed on steep rocky cliffs, because this protects them from four-footed predators, such as fox and rats. Inaccessible rocky islands are ideal. You usually find puffins and gannets at the top of the rocks. The dominating winds make it easier for them to take flight. Puffins breed in holes. Guillemots and razorbills lay their eggs on the lower lying rocky ridges.

Seabird migration

Some seabird species stay the entire year in the vicinity of their nesting area. Others migrate elsewhere. Gannets and puffins leave the North Sea area. There are four species that stay the entire year in the North Sea: fulmar, kittiwake, guillemot and auk. They don’t stay in one place but move around within the North Sea region. Guillemots make their nests along the English and Scottish northern and eastern coast and migrate in August with their young chicks to the eastern or southern part of the North Sea.

As foraging area in the winter, the southern North Sea is particularly important for seabirds. The Frisian Front in particular, an area north of the Wadden Islands, attracts many seabirds. The tidal currents are so weak here that nutrient-rich mud settles to the bottom. Therefore, there are lots of benthic fauna, fish and seabirds.

It’s difficult to see seabird migration along the Dutch beaches. The birds fly along the coast, but too far away to observe easily. Only with stormy northwestern winds do they fly closer to the coast. This is when unusual seabird reports are made. During such conditions, warmly dressed bird watchers with telescopes can be found scanning the rough seas.

Seabirds at the top of the food chain

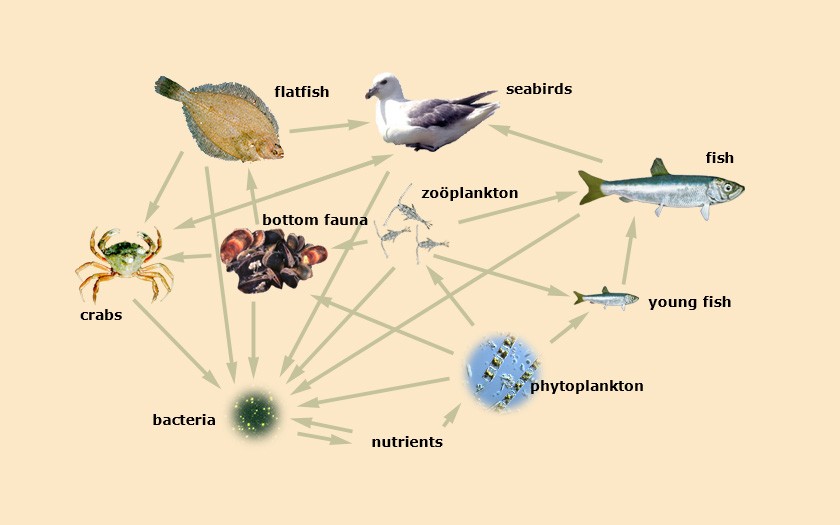

At the base of life in the sea are the microscopically small plants, the phytoplankton. In addition to water and carbon dioxide, they also need sunlight and nutrients in order to grow. The phytoplankton are consumed by the zooplankton, mostly small animals which float around in the water. The zooplankton are eaten by all kinds of benthic animals and fish, which in turn are eaten by larger fish. All of these fish eventually end up on the menu for marine mammals, people and seabirds. Seabirds belong to the top of the food chain. They eat mainly small fish such as sprat and lesser sandeel. Only the gannet eats larger fish, such as mackerel.

From studies of kittiwakes in Alaska, it became clear how important a good diet is for this gull species. The kittiwake population in this area has declined by 50% since the 1980s. At the same time, there was also a reduced availability of fatty fish species due to climate change. It appeared that brain development is caused by a lack of sufficient fatty fish, whereby the young kittiwakes are probably too ‘stupid’ to survive.

Hunting of seabirds

Seabirds aren’t really very tasty for people; nevertheless, they used to be hunted and eaten. The eggs are tasty, so these were the most popular. Usually, those that gathered the eggs made sure that enough remained behind to ensure a continual production. Otherwise, they would lose their livelihood.

It was a different story for the great auk. This seabird could not fly. It lived in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean. In the 19th century, they were slaughtered on a large scale as food for the seal hunters and fishermen. The specimen was killed in 1844.

There are still people who eat seabirds. On Iceland and the Faroe Islands, where seabirds used to be an essential source of food, the residents still eat puffins. The birds are caught with the help of nets on poles. This is called ‘fleyging’. It takes place on boats or by standing on steep cliffs of the nesting colony. The birds are caught in the air when they fly close along the cliffs on the way to their nest.

Seabirds threatened by poisoning

Pollution in seawater with all kinds of toxic materials is also a big threat for seabirds. Toxic materials are found in many variations: heavy metals, pesticides, PCBs, PAHs, UGILECs, etc. These harmful materials enter the sea from the rivers, through accidents, discharges and incineration at sea, and even via precipitation from the air.

Via the food chain, the toxic materials are carried up the line to the seabirds, where the materials accumulate in their fatty tissue. Extra deaths of seabirds occur during breeding season and the winter months, when the birds address their fat reserves. It is known that the hormone balance is disturbed by the pesticide DDT. The production of calcium decreases. Calcium is found in egg shells. Because of DDT, these shells are thinner and break more readily. In Florida, breeding pelicans sagged through their own eggs as a result of DDT pollution.

It has been proven that PCBs disrupt the reproduction of birds and mammals. They are also harmful for the immunity system whereby the animals become sick more readily. Sometimes, the amount of PCBs in the fatty tissue of some seabirds has grown to tens of thousand times higher than in the seawater itself.

Seabirds covered in oil

Oil is the biggest threat for seabirds. Every year, tens of thousands of seabirds die from oil pollution in the Dutch section of the North Sea alone! Only a fraction of these victims can be saved in the coastal rehabilitation centers, such as Ecomare.

Seabirds and fisheries: friend…

Some seabirds profit from the fisheries. The fact that larger fish species such as herring, mackerel and cod are caught in massive numbers, smaller fish don’t have as many predators and have less competition for food. Species such as lesser sandeel and sprat have been able to grow in number. Fulmars, kittiwakes and guillemots in particular have profited from the disturbed situation. In the 20th century, partially thanks to the abundance of the available food, these seabird species have made a spectacular recovery from the hunting and egg collection which reduced their numbers at the end of the 19th century.

Many seabirds profit from the fish wastes thrown overboard by the fishermen. Kittiwakes and fulmars in particular have no problem tracking down the fishing boats.

…and enemy!

Seabirds drown regularly in the nets of the standing rigging fisheries. By the Norwegian coast, this seems to be the cause of death for around 30,000 guillemots every year.

In the 1980s, an end seemed in sight for the growth of the seabird population in the North Sea due to the arrival of the industrial fisheries. This sector catches small fish such as lesser sandeel and sprat, which is food for many of these birds. After 1982, the lesser sandeel around the Shetland Islands declined in number. Since 1983, Arctic terns, Arctic skuas, kittiwakes, puffins and fulmars have had poorer nesting results due to the food shortage.

It cannot be proven that the fisheries are the only cause of the problem. It’s possible that a change in the current pattern of the water also plays a role. In the Netherlands, starved guillemots, auks and kittiwakes were found during the winters in the 1980s.

Lobbying for seabirds

A number of environmental groups have been concerned about the future of seabirds in and around the North Sea. The National Committee for Oil-free Seabirds – a joint program between the Dutch Bird Society, the Dutch Society for the Protection of Animals and coastal animal kennels – supports bird sanctuaries with funds for good accommodation and food during disasters involving birds. The group includes Greenpeace, the North Sea Foundation and the Wadden Sea Society. Via campaigns and lobbying, these groups attempt to educate politicians and the public on the deteriorating living conditions for seabirds in the North Sea region.

There is not very much known about the distribution of seabirds around the North Sea, their choice of food and the best way to protect them. Observations during sea expeditions from people counting birds must supply more clarity.

The scientists are also looking at the effects of pollution in the North Sea environment. Such studies are very important because the governments of the North Sea countries want to see proof before taking any steps. The Dutch Workgroup for oil victims (a division of the Dutch Seabird Group) studies the effects of oil pollution on seabirds. Seabirds are also examined internally in the Netherlands and other North Sea countries. In this way, additional data on the effects of oil and floating plastic is obtained.

Facts about seabirds

- number of species worldwide:

more than 300 - number of species in North Sea:

around 30 - largest North Sea bird species:

gannet, wingspan: 2 meters - smallest North Sea bird species:

petrel, wingspan 40 centimeters - enemies:

humans (competition with fisheries, hunting, pollution), raptors and disease and occasionally a seal - food:

fish, crustaceans, zooplankton, shellfish, young birds

Names

- Dut: zeevogels

- Eng: seabirds, marine birds

- Fre: oiseaux de mer

- Ger: Meeresvögel, Seevögel

- Dan: havfugle