During the Middle Ages, porpoises were called mereswines, or ‘sea pigs’. In those days, they were consumed a lot. There was a huge population living along the Dutch coast. Those were the days when anchovies and other small fatty fish were plentiful. The porpoises followed the fish into harbors, which is why they are officially called harbor porpoises. Porpoises grew scarcer halfway through the 20th century, however the number of sightings since 1995 have increased tremendously. The porpoise is presently the most common cetacean in the North Sea.

Spotting porpoises

It’s not easy to spot porpoises at sea. Unlike other dolphins, porpoises rarely jump out of the water. You’re not likely to see more than the top part of its back with its dorsal fin when surfacing for a breath of air. Porpoises live either alone or in groups of three to five animals; sometimes more. If you spot two animals together, chances are it’s a mother and calf. They sometimes form large groups when migrating. From land or from a (ferry) boat, the most likely time to spot a porpoise is in the winter.

Porpoises are back again

Up till the mid 1900s, there were several places along the coast where you could spot porpoises, such as in the Marsdiep. However, the situation changed between 1950 and 1980. Pollution, particularly PCBs, caused a sharp decline in the population along all of the coastal areas of the southern North Sea. Intensified fishing of small fish species resulted in a decrease in available food for the porpoises. Furthermore, more and more animals became entangled in fishing nets.

Since 1995, many porpoises have again been regularly spotted along the coast. The population in the southern North Sea grew so fast that it could not just be attributed to new births. Extensive counts from sea-going vessels in 1994 and 2005 showed that the total number of porpoises in the North Sea fluctuated in both years at around 250,000 animals. Two-thirds of the population swam in the northern North Sea in 1994, while just the opposite was found in 2005, where two-thirds were found in the southern North Sea. The number of fish-consuming birds in the northern North Sea also declined, so scientists assume that the porpoises left the region to find new sources of food.

Population of porpoises in the Dutch North Sea

Up till recently, no one knew exactly how many porpoises swim in the Dutch part of the North Sea. Researchers from IMARES have made the first complete estimate, using airplane counts. In March 2011, they counted a minimum of 85,572 of these small toothed whales in the Dutch part of the North Sea. That amount is about half of the entire porpoise population in the southern North Sea!

The number of porpoises in the entire Dutch part of the North Sea fluctuates per season. In March 2011, there were three times as many porpoises counted as in the summer and autumn of 2010. They only counted 30,000 animals then. The greatest chance of seeing porpoises is in the winter. In all seasons, the researchers saw the greatest numbers in the area between the Brown Bank and the Borkumer Stones. The most calves were seen in July. According to the researchers, this confirms the assumption that porpoises also produce young here.

Distribution of porpoises

The porpoise lives in all shallow, relatively cold coastal seas. There are around 250,000 porpoises living in the entire North Sea, of which tens of thousands in Dutch waters. When there were lots of anchovies around, porpoises were also numerous in the Zuiderzee and Wadden Sea. Nowadays, they are a rarity.

Porpoises in the Zeeland Delta

In Zeeland, a surprising number of porpoises have been spotted in recent years. The Westerschelde has an open connection to the sea, but the Oosterschelde is partially closed off by the storm surge barrier. Therefore in the Oosterschelde, it is unclear whether there is a permanent group or if the porpoises are swimming in and out via the barrier.

Studies have shown that the porpoises in the Oosterschelde definitely don’t swim regularly back and forth to the North Sea. That can be a problem, since the mortality rate in the Oosterschelde is higher than in the North Sea. It’s possible that the porpoises in the Oosterschelde can’t find enough fish to eat. Studies show that the dead porpoises lived off of a lean and one-sided diet. In 2010, scientists saw porpoise calves that were so young, that it’s very likely they were born in the Oosterschelde.

What’s very exceptional ar the reports of porpoises in the Grevelingenmeer. This former sea channel has been closed off to the sea by the Grevelingen dam and the Brouwers dam. The first sighting of a porpoise was in 2006, but regular reports followed, including photos. It is probably the same animal. This porpoise is very tame and often swims with sailboats.

Porpoise diet

Porpoises find their food under water with the help of sonar. In the coastal region of the Netherlands and the Baltic Sea, they eat mainly small benthic fish such as gobies. In the open North Sea they feed mostly on herring, sprat and mackerel. Porpoises in the German Wadden Sea go after small flatfish. Large flatfish are dangerous for porpoises; various porpoises that have washed ashore were found to have choked to death after eating large flatfish.

Twenty years ago, porpoises in the North Sea ate mainly whiting. However, this fish species is not that prominent anymore. That is why they have switched over to gobies. Gobies are much smaller than whiting, so they need to catch much more to satisfy their needs. Scientists have found that porpoises that strand in the summer seem to have problems finding sufficient food. Porpoises eat around five kilograms of fish daily – this is 10% of their body weight. There is a theory that porpoises help each other to look for food using their sonar system. You can imagine that it is easier to find food in a large sea when the group is spread out.

Mating season for porpoises

Porpoises mate in the period June to the beginning of August. Calves are born 11 months later so that the birthing peak is in July. Females are sexually mature between 5 to 6 years old. Most females do not bear young every year. Calves are nursed for around 8 months, after which they switch to a fish diet. That’s not always an easy process: many young porpoises often have trouble finding enough to eat. Most of the stranded porpoises found along the beach are not much older than one year. At that age, they are around 100 centimeters long.

Porpoise calves

Calves are nursed for around 8 months, although they will try a fish as well during that period. This time is necessary for the calf to learn the tricks of the trade from its mother. Workers on a gas production platform witnessed these lessons in September 2011. The mother stayed with her calf for a number of weeks under the platform. The workers saw how the calf was nursed and how the mother regularly brought fish to the surface, which was then release close to the rapidly approaching young. The calf then attempted to catch the fish. Sometimes it was successful, but not always.

After the nursing period, the calf switches to a diet of fish. That’s not always an easy process: many young porpoises often have trouble finding enough to eat. Most of the stranded porpoises found along the beach are not much older than one year. At that age, they are around 100 centimeters long.

Whale louse and porpoises

Whale louse is a kind of crustacean, but it isn’t as innocent as it sounds. It is a true parasite. The creatures eat the skin, fat and blood of their hosts, in this case porpoises. They survive particularly on sick and weakened animals, causing lots of problems for these victims. Whale louse can accumulate around a wound, for example. Healthy porpoises make sure that these pests don’t get a chance by scratching sufficiently to get rid of them.

Strandings of porpoises and research

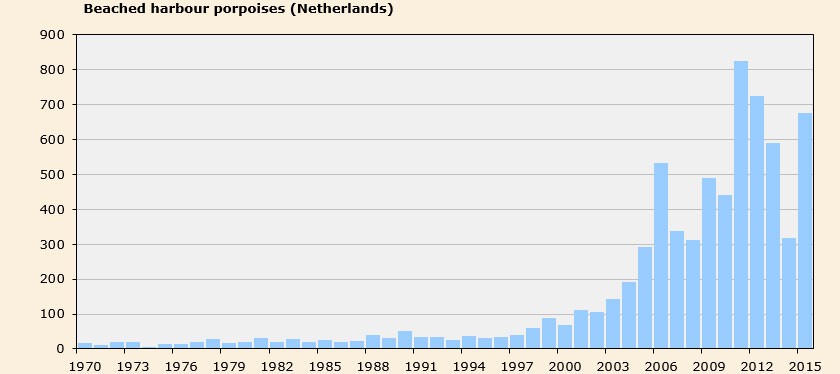

Even though the Netherlands coastline is short, many porpoises beach along the Dutch shores. On the average since 2004, around 400 animals per year are found, while surrounding countries find much less. For example, while the coast of Great Britain is 30 times longer than the Dutch coast, ‘only’ 200 strand there. The numbers found in France and Denmark are much less, around 130 per year. It is unclear why so many porpoises wash ashore in the Netherlands. Are there more porpoises swimming off these shores or do more die here? Is it easier to find stranded animals here or does the sea current play a role?

The number of stranded porpoises fluctuates strongly every year. This is probably related to the migration movements of the porpoises: when there are lots of fish off the Dutch coast, there are many porpoises and more animals run into problems.

Protection of porpoises

A porpoise reservation has been established west of Sylt because so many calves are born there every year. In the Netherlands, porpoises are listed as protected animals in the Habitat Directive. Since 2010, the Dutch Ministry for nature has been working on a species protection plan for the porpoise. The Royal Dutch Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) has prepared a research plan for this purpose.

Dangers for porpoises

In 2006, a large group of scientists performed autopsies to establish the cause of death in stranded porpoises. The results showed that more than half of the animals died from drowning. Most likely, they became entangled in fishing nets from gill, trammel and standing rigging. A similar study in Denmark in 1974 showed that thousands of porpoises were victims of standing rigging nets. The drowned animals were otherwise healthy and their stomachs were often full. Drowning occurred mostly in March and April.

In 2006, a large group of scientists performed autopsies to establish the cause of death in stranded porpoises. The results showed that more than half of the animals died from drowning. Most likely, they became entangled in fishing nets from gill, trammel and standing rigging. A similar study in Denmark in 1974 showed that thousands of porpoises were victims of standing rigging nets. The drowned animals were otherwise healthy and their stomachs were often full. Drowning occurred mostly in March and April.

A second major cause of death was contagious diseases. These sick animals, with little fatty reserves and an empty stomach, washed ashore mostly in August. In 2007, the seal creche in Pieterburen performed its own internal study, commissioned by the Dutch Fishery Union. In this study, the proportion of drowned porpoises was less. Other important causes of death in that study were pneumonia and starvation.

Studies on the fatty layer of freshly stranded porpoises showed that they contained lots of toxic substances, such as a poisonous flame retardant. This substance is used in insulation foam and upholstery. The poison ends up in the sea via waste water and ‘consumed’ by fish. Because porpoises eat lots of fish in their lifespan, large amounts of this poison eventually build up in their blubber. This toxic material disrupts the animal’s thyroid metabolism and functioning of its nervous system.

Pingers and porpoises

More and more fishermen are attaching underwater loud speakers to their fishing nets to keep porpoises at a distance. These ‘pingers’ transmit sounds which scare the animals. Since 2007, pingers have been required for fishing vessels larger than 12 meters that fish with gill and trammel nets. However, there are also disadvantages to using pingers. In some cases, the marine mammals learn that the sound is made in an area where they can easily snatch up fish. Then the pinger works more as a dinner bell and that makes it dangerous for the porpoises.

Stranded porpoises with strange wounds

Sometimes a badly mutilated porpoises wash ashore. In 2009, one third of all the stranded porpoises had large long cuts on their bodies. For a long time, the cause of these wounds was a mystery. Belgian scientists then discovered that most of the wounds resembled bites from predators. The distance between the incisors corresponds with the teeth of the grey seal. The actual evidence came from the laboratory at NIOZ on Texel: scientists found DNA from grey seals in the wounds. That shows that adult grey seals are truly predators: they can even catch porpoises.

Porpoises on and around Texel

Porpoises are regularly spotted in the waters around the island, particularly in early spring. At Ecomare, you can see the small cetaceans the entire year. Since 2012, two porpoises swim in a basin at the center, specifically built for porpoises. They can even be observed underwater, through special windows… although, who’s actually looking at whom?

Facts about porpoises

- size:

maximum 190 centimeters (at birth 70-80 centimeters)

- weight:

up to 60 kilograms (at birth around 5 kilograms)

- color:

Dark gray back, light grey sides with dark spots, white chin and belly

- age:

12 to 15 years

- food:

fish, such as gobies, herring, sprat, mackerel, whiting and cod; cuttlefish, crabs, worms and snailsp

- movement:

dive: 4-6 minutes down to 200 meters deep

speed: maximum 23 kilometers per hour

- enemies:

man: tangled in nets, loss of habitat, pollution and acoustic noise.

animals: grey seals, dolphins and killer whales

- reproduction:

maturity: 3-6 years old

frequency: once every 1-2 years 1 calf

pregnancy: 10-11 months

nursing: 7-8 months

Names

- Dut: Bruinvis (gewone bruinvis, varken)

- Lat: Phocoena phocoena

- Eng: Harbor porpoise (common porpoise)

- Fren: marsouin

- Ger: Schweinswal (Braunfisch, Meerschwein, Kleiner Tümmler)

- Dan: Almindeligt marsvin

- Nor: Nise

WWW