Animals of the mud flats

At first, you don’t see much on the bottom of the North Sea. However, appearances are deceptive: most of the residents are hiding. Worms, crustaceans and shellfish live in holes and tunnels under the surface of the sea floor. If you look closely, you can identify quite a lot of life on the bottom: crabs and sea snails, such as laver spire shells and periwinkles, crawl around. Lots of other animals are attached to stones or ship wrecks. All the different areas in the North Sea have their own characteristic species of animals.

Benthic fauna: at home in sand and mud

The majority of the North Sea bottom consists of sand and silt. A lot of animals live burrowed in the bottom, such as worms and shellfish. Some worms, such as rag-worms, dig their way through the bottom. Others live in tubes that stick out just above the floor surface, for example, the Pygospio elegans. Its tube is built up of sand grains stuck together with slime.

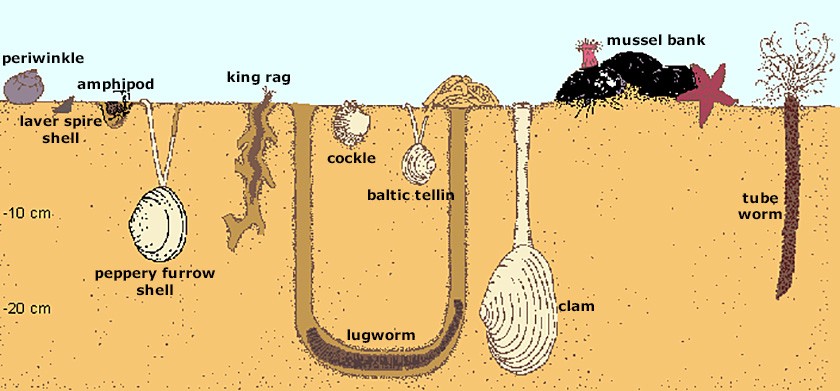

Most species of shellfish live in the bottom. They maintain contact with the surface via their siphons. Seawater flows in and out of these tubes. The animals use the oxygen in the water and filter out the nutrients. Well known examples of shellfish living in the bottom are the Baltic tellin, the cockle and the gaper.

Sea bottoms with lots of mud contain more animals and a greater variety of species, which you won’t find in sandy bottoms.

Benthic fauna on hard bottoms

Rocky bottoms are not very common in the North Sea. You find them mostly in the vicinity of Calais and by Scotland and Norway. There are stony fields and gravel beds sparsely spread throughout the North Sea. These are old river beds dating back to the last glacial period, when the North Sea was empty of water. These rocky environments form homes for animals which rely on hard surfaces.

Barnacles, mussels, sea anemones and sponges spend their life attached to rocks and stones. Crabs and lobsters like to hide between stones. These ‘rock’ inhabitants are also found in ‘artificial rocky areas’, for example in marine harbors, on or in the vicinity of shipwrecks, and at the foot of breakwaters.

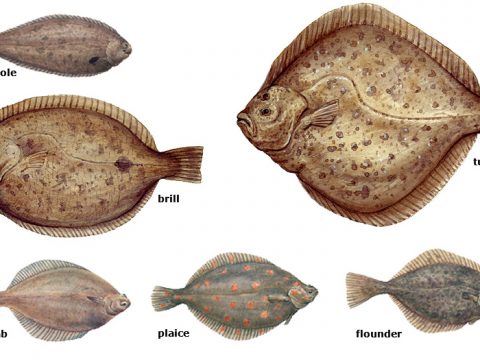

There’s another group of bottom inhabitants crawling over the bottom. This group consists mostly of scavengers and carrion eaters such as crabs, starfish and sea urchins. Flatfish and rays also belong to this category. These fish, such as plaice and sole, live on the sea floor and feed on benthic animals and small fish. They often have a color pattern similar to the seabed where they reside in order to camouflage themselves better. Turbot are even capable of adapting their color to their environment! Benthic fish dig themselves in.

Benthic fauna: filter feeders, vacuum cleaners and sand consumers

Benthic animals have all kinds of methods to sieve food out of the water, siphon it from the floor or graze. Filter feeders, such as sand masons, sieve food particles out of the water. By sticking their tentacles out of their tube, they catch food particles with a sticky fluid which covers the tentacles. Shellfish gather food particles using their gills, which are covered with vibrating hairs. Various crustaceans and shrimp graze from the floor. One example is the mud shrimp Callianassa. Callianassa live off of bacteria which in turn live on the linings of their tunnel complexes.

Benthic fauna: predators and scavengers

In the sea bottom, there are animals crawling around which eat other benthic animals, dead or alive. Most predators and scavengers live on the bottom, such as shrimp, crabs and fish. The starfish uses its suction feet not only to move around but also to catch mussels. It can break open a mussel by placing two arms on the left valve and the other arms on the right valve. The mussel closes its valves with its strong constrictor muscle, however the starfish waits patiently. When the mussel tires, the starfish begins to pull, and after holding out for a few hours, the shell halves will separate. The starfish everts its stomach into the shell and digests the mussel.

Common dogwhelks and necklace shells eat other molluscs and barnacles. Using a combination of a grating tongue and a dissolving acid, the snail drills a hole into the victim’s shell. The snail then devours the soft animal in the shell. On the beach, you often find shells with a nice round hole. You now know how its inhabitant’s life was ended.

Dead algae and marine animals also end up on the sea floor, together with excretions from live animals. This forms food for a large amount of bacteria, which break down the nutrients into silicic acid, nitrate and phosphate. These nutrients are necessary for the phytoplankton to grow.

Benthic fauna in tidal areas

The animals that live on the muddy tidal bottom are true die-hards. They must be resistant to heat and cold, salt and freshwater, exposure and anaerobic mud. Those that are capable of surviving under these extreme conditions can benefit tremendously from the large amount of food brought in twice a day with the tides. Some species of shellfish, worms and crustaceans have become specialists. There are not many species, but there are enormous numbers per species. It is the world of mussels and oysters, corophium, cockles, gapers, lugworms, ragworms and the threadlike Heteromastus filiformis worms.

Difficult life for benthic fauna

Benthic animals have to deal with extreme conditions in tidal areas. First of all, the mud flats are exposed twice a day. There are sharp fluctuations in temperature and salinity. Some animals avoid the misery by temporarily going elsewhere. Shrimp and crabs move to the channels during low tide and return to the banks during flood. In the autumn, they migrate to the open sea. Other animals protect themselves from the cold by burrowing deep into the bottom. The slender ragworm (Nereis pelagica) burrows down to 60 centimeters under the surface in the winter. Cockles prevent themselves from freezing by releasing a substance which works as anti-freeze. Despite this precaution, many cockles will freeze to death during severe winters. That holds true for heat waves and extremely heavy storms.

Benthic fauna: filter feeder or grazer?

Many benthic animals eat plankton; others eat the remnants of dead sea inhabitants. They have developed all kinds of methods for catching their food.

Filter feeders filter their food particles out of the water. Pygospio elegans (a tube worm) sticks its tentacles out of its tube. There is a sticky material on the tentacles upon which the food particles stick. Mussels and oysters use their gills as a sieve, which are covered in ciliate (trilling hairs). The ciliate help transport the food to the mouth.

Not all shellfish are exclusively filter feeders. For example, Baltic tellins use a ‘vacuum cleaner’: they have a long and movable inflowing siphon, with which they sweep the floor surface and suck up food particles.

Lugworms eat the muddy particles while digging. They digest the edible parts and excrete the rest. The excrement looks like a pile of spaghetti. In order to get enough food, these worms must eat a lot of sand. They live in a U-shaped tube. At one end, the animal eats up the sand, forming a crater on the surface. The piles of spaghetti lie at the other end.

The amphipod Corophium volutator, which lives in a tunnel in the mud flats, occasionally comes out of its tunnel to scrape off the top layer of the surface with its two long antennae. He takes his catch into his tunnel where he examines it for anything edible. The inedible material is redeposited outside his tunnel.

There are also grazers. They eat small algae lying on the surface. Laver spire shells and periwinkles crawl over the bottom like a cow grazing in a pasture.